Written By: Uroosa

Global warming is no longer an abstract global debate for South Asia; it is a daily reality shaping weather, livelihoods, and national security across the region. Countries like Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka are already experiencing the harsh consequences of a warming planet, despite contributing only a small share to global greenhouse gas emissions. The steady rise in global temperatures, driven mainly by human activities such as fossil fuel consumption, deforestation, and unplanned urban growth, has placed South Asia among the most climate-vulnerable regions in the world.

Global Warming Impact

At a global level, average temperatures have increased by more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, with recent years breaking heat records worldwide. For South Asia, this warming translates into longer summers, shorter winters, unpredictable monsoons, and extreme heatwaves. Pakistan, in particular, has witnessed some of the highest temperatures ever recorded on Earth, with cities like Jacobabad and Turbat repeatedly crossing human survivability thresholds during summer months.

Global Warming in Pakistan

One of the most visible impacts of Global Warming in Pakistan is the growing intensity of heatwaves. Over the past decade, heat-related illnesses and deaths have increased, particularly in urban centers where poor housing, power shortages, and limited access to clean water worsen the situation. The 2015 Karachi heatwave, which claimed over a thousand lives, was an early warning. Since then, similar conditions have become more frequent, highlighting how climate change directly threatens public health.

MoonSoon System Effects on Agriculture

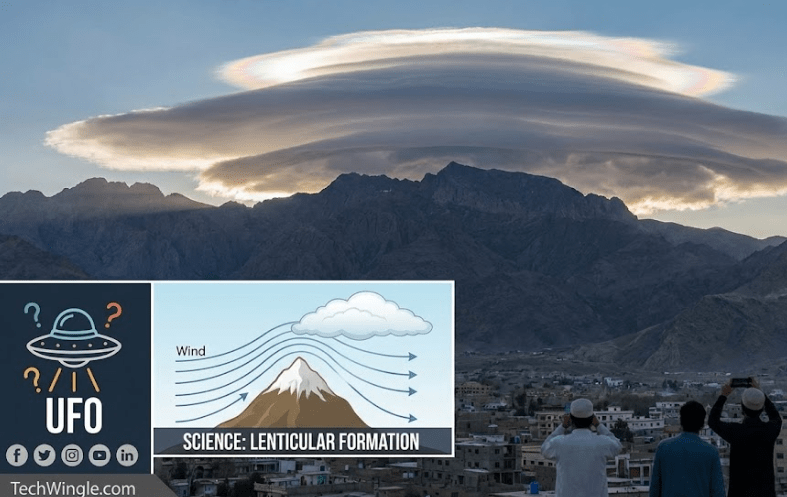

Another major consequence is the increasing instability of the monsoon system, which is the backbone of South Asia’s agriculture. Rainfall patterns have become erratic, either arriving too late, too early, or in destructive bursts. Pakistan’s 2022 floods, which submerged nearly one-third of the country and affected over 30 million people, exposed the devastating link between global warming and extreme weather. Scientists later confirmed that climate change significantly intensified the rainfall, turning a natural monsoon into a national catastrophe.

Melting glaciers in the Hindu Kush–Karakoram–Himalayan region present another serious concern. Pakistan has more glaciers than any country outside the polar regions, and rising temperatures are accelerating glacier melt. While short-term melting increases flood risks, long-term glacier loss threatens water security for millions who depend on rivers like the Indus. Reduced water availability would directly impact agriculture, hydropower generation, and food security across the country.

Global Warming Quietly Reshaping Rural Life

Global warming is also quietly reshaping rural life. Agriculture employs a large portion of Pakistan’s population, yet it remains highly sensitive to temperature changes and water stress. Rising heat levels reduce crop yields, damage soil quality, and increase water evaporation. Farmers now face unfamiliar pests, crop diseases, and unpredictable growing seasons. These pressures contribute to rural poverty, food inflation, and internal migration toward already crowded cities.

Air Pollution in Human Lives

Air pollution, closely linked to climate change, has worsened living conditions in South Asia. Major Pakistani cities consistently rank among the most polluted globally. Warmer temperatures trap pollutants for longer periods, intensifying smog during winter months. This has led to a rise in respiratory diseases, particularly among children and the elderly, placing further strain on an already burdened healthcare system.

The economic cost of global warming is becoming increasingly visible. Climate-related disasters have caused billions of dollars in losses for Pakistan, diverting resources from education, healthcare, and development. Infrastructure damage, crop losses, and emergency relief efforts slow economic growth and deepen inequality. Experts warn that without serious climate adaptation measures, climate shocks could erase years of development progress.

What makes the situation particularly unjust is that Pakistan contributes less than one percent to global carbon emissions, yet ranks among the most climate-affected countries. This imbalance highlights the ethical dimension of climate change and strengthens Pakistan’s call for climate finance, loss-and-damage compensation, and fair global responsibility-sharing.

Environmental degradation is another growing concern. Forest loss, rising temperatures, and water scarcity are disrupting ecosystems and biodiversity. Mangrove forests along Pakistan’s coast, vital for protecting against cyclones and sea intrusion, are under stress from rising sea levels and warming waters. Coastal communities in Sindh and Balochistan already face displacement as seawater encroaches on farmland and freshwater supplies.

Despite these challenges, Pakistan and other South Asian states have begun taking steps toward climate resilience. Investments in renewable energy, tree plantation drives, climate-smart agriculture, and disaster preparedness signal growing awareness. However, these efforts remain insufficient without strong political commitment, regional cooperation, and sustained international support.

Cinclusion

In conclusion, global warming is not a distant or foreign issue for South Asia and Pakistan. It is altering weather systems, threatening food and water security, damaging health, and deepening economic vulnerabilities. Addressing this crisis requires more than global promises; it demands urgent local action, climate-resilient planning, and international climate justice. The choices made today will determine whether future generations inherit a livable region or one permanently shaped by climate extremes. Read More